Eventually I realized that when I receive a GPG encrypted email, it simply means that the email was written by someone who would voluntarily use GPG. I don’t mean someone who cares about privacy, because I think we all care about privacy. There just seems to be something particular about people who try GPG and conclude that it’s a realistic path to introducing private communication in their lives for casual correspondence with strangers.

Increasingly, it’s a club that I don’t want to belong to anymore.

The Decemberists at Paradiso, Monday 23 Feb 2015

After having raved at him for years about how great a gig venue Paradiso is, I finally managed to lure Alan across to the Netherlands for a couple of days last week, so we could see The Decemberists. On Monday we spent the afternoon wandering around Amsterdam. Lunch at De Brabantse Aap, hot chocolate and a brownie at Bagels and Beans on the Keizersgracht, and a beer or two at Café Hans en Grietje on the Spiegelgracht. Abi caught up with us there after work, and we had a steak at Los Argentinos before heading over to Paradiso. We were just too late for the support act (Serafina Steer), but in plenty of time for the Decemberists.

Set list:

- The Singer Addresses His Audience

- Cavalry Captain

- Down By The Water

- Calamity Song

- Grace Cathedral Hill

- Philomena

- The Wrong Year

- The Island: Come And See / The Landlord’s Daughter / You’ll Not Feel The Drowning

- Los Angeles, I’m Yours

- Carolina Low

- The Sporting Life

- The Rake’s Song

- Make You Better

- (Rock T-Shirt Challenge)

- The Legionnaire’s Lament

- 16 Military Wives

- Oh Valencia

Encore 1:

- 12/17/12

- A Beginning Song

Encore 2:

- The Mariner’s Revenge Song

Good audience participation on “16 Military Wives” and “The Mariner’s Revenge Song” – they seems to be perennial favourites. I didn’t know “The Mariner’s Revenge Song” when Abi and I went to see them a few years ago, but I knew what to expect this time round. I’d been hoping for more songs from The Hazards of Love, and Abi would have liked them to play June Hymn, but it was a good, long, and varied set (they were on stage for the best part of two hours). Definitely worth catching them live.

NYC

I’m in New York!

It’s really cold!

I’m staying at the Broadway Plaza Hotel on 27th and Broadway. After I got here and dropped my bags, I called Abi, then went out for a walk. I’m trying to stay up until around 21:00, to try and force my system into the right time zone. (Abi wisely suggested I bring one of her custom-made USB blue light boxes with her, which I’ll use tomorrow morning.)

I walked North to 32nd Street, and stopped in at JHU Comics, where I picked up volume 4 of Saga, volume 8 of Ex Machina (not new – I’m still catching up on it), and volume 1 of Rat Queens.

Being on a low-FODMAP diet I know I’m going to regret this, but I stopped off for a slice of pizza at Empire Pizza on 5th Ave on my way South again. It was cold, I was hungry, I was weak. It was really good.

Perhaps inadvisably given the cold and my illness-ridden state, I walked down to Union Square then looped back to the hotel. I couldn’t feel my face by the time I got back. Fortunately the hotel supplies hot water, and I brought my own supply of lemsip. AND IT’S WARM IN THE ROOM. Unlike many hotels in Edinburgh, this one reckons that heating is not an optional extra in the middle of winter.

La Roux at Paradiso, Wednesday 10 December 2014

Given that this was the blow-out last night of the European tour for their album called Trouble in Paradise, if La Roux don’t release a live recording of this show and call it “Trouble in Paradiso”, they are seriously missing a trick. I’m hopeful for this because after the opening act (Meanwhile) their support crew spent a full hour working on the most elaborate sound check I’ve ever seen at Paradiso.

It was worth the wait. The band walked on dressed in sharp suits (the drummer even sporting a tidy pocket square), looking cool as cucumbers, and proceeded to play an immaculate set. Tight and precise, but not clinical. On the opening lines of “Let Me Down Gently” I thought Elly Jackson’s voice cracked a bit, but she soon warmed up and sounded amazing for the rest of the gig. She reminded me of 1980s-era Bowie with her side-to-side stepping dance moves and casual flips of her striped jacket. She projected a cool and confident, somewhat haughty poise to match the look, but every now and then she would let a shy, sweet smile break through. It was adorable.

Set list:

- Let Me Down Gently

- Fascination

- Kiss And Not Tell

- In For The Kill

- Sexotheque

- Cruel Sexuality

- I’m Not Your Toy

- Shame Shame Shame (cover of Shirley & Co.)

- Tropical Chancer

- Uptight Downtown

- Colourless Colour

- Silent Partner (Already a 7-minute romp on the album, they turned this into a 10-minute drum-laden extravaganza, with the perfectly groomed drummer going absolutely mental, and Elly triggering the siren sounds on a pair of extra pads mid-stage. A fantastic finale.)

- Tigerlily

- Bulletproof

Mixed Media, Saturday 31 January 2015

Last Mixed Media post I said how much I was enjoying the start of season 2 of Arrow. The rest of the season was just as good – a roller-coaster ride from start to finish. There was no “filler” where Oliver Queen just hunted some bad guys. Every episode had something new and exciting to offer.

After binge-watching my way through Arrow I needed something else to sink my teeth into, so I wolfed down season one of Broadchurch. Very different from Arrow, but no less gripping and compulsively watchable. After that I jumped into Person of Interest…and ground to a halt. I’d heard so many good things about it, but compared to Arrow and Broadchurch it’s really dull. I’ve watched up to episode nine or ten, and so far it’s all villain-of-the-week stuff. A longer-term story arc involving the up-and-coming organized crime boss Elias is starting to take shape, but it’s moving at a glacial pace. The relationships between the characters aren’t changing or evolving at all. Maybe it gets better in later seasons, but I’m not sure if I’ll actually make it there.

(Also: in the early episodes of Continuum I found myself regularly annoyed by the crinimally fake depth-of-field effects applied in post-production. Blur for the sake of blur. Similarly, Jim Caviezel’s additional dialogue recording in PoI is terrible, and makes me grind my teeth whenever I hear another poorly edited cut.)

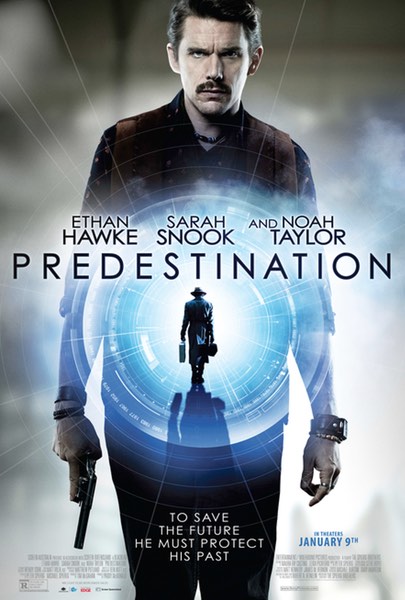

On my trip to Edinburgh last week I watched Gone Girl on the outbound flight, and Predestination on the return leg. I love David Fincher’s films, and I had hoped to catch Gone Girl in the cinema, but I didn’t quite make it. I haven’t read the book, but I knew the premiss. The first hour played out about as I had expected, but then it took a bunch of twists I hadn’t seen coming. The opening and closing shots are amazing bookends. Tony Zhou’s episode of Every Frame a Painting on Fincher gave me a lot to think about while watching the film, too:

Predestination is a subtle, clever, and twisty time travel story with a great lead performance by Sarah Snook. You kinda know where things are going to go, but how it gets there is patient, framed with empathy for characters who have to make sometimes awful choices. It’s not an action movie romp. The first half of the film is basically two characters talking in a bar, one narrating flashbacks of his own life story. But it’s content to tell a tall tale without being rushed. I liked it a lot.

I hadn’t listened to Lizzo for a while, so I spun up her album LIZZOBANGERS last week. Then I visisted her site to see if she had anything new cooking, and I found this track with Caroline Smith. Is it not happy and wonderful?

Searching for more Caroline Smith then led me to the album Pangaea by Toki Wright and Big Cats, the earlier album For My Mother by Big Cats, and Caroline Smith’s own album Half About Being a Woman. Good finds, all.

I’m still reading Harry Connolly’s The Way Into Chaos. To be honest I was disappointed by the start. Epic Fantasy isn’t normally my thing, and I found it hard to get on board with the unfamiliar titles and stilted courtly speech. The opening chapters also felt slightly simplistic, and somewhat young-adulty. I have nothing against young adult fiction, and I enjoy reading it; but it wasn’t what I had been expecting from the Great Way series. Also, being a kickstarter backer I was reading the book with writing a glowing promotional review in mind, and I just wasn’t feeling it — which made me feel reluctant about picking it up again each time…

However, with all that out of the way, something changed in chapter 12, and I found the characters coming alive for me. Cazia was making decisions of her own, rather than being propelled by events. Rescuing Vilavivianna gave her the opportunity to be a leader rather than a follower. Her increased agency made her more interesting as a protagonist. Since that point, I’ve found it more difficult to put the book down than to pick it up. It has found its stride.

Mathematical impressions

On a meandering journey that ultimately started with a remaindered link on Kottke, I came across this nice series of mathematical diversion videos: Mathematical Impressions by the Simons Foundation. Here’s one about spontaneous stratification: