Hacked, grr

Late this afternoon, I happened to do a Google search for something I had written on my blog last year. The article came up in the search results, but when I clicked on it, I was redirected to a different site (a .ru domain). The target page didn’t load, though.

Primary investigative steps:

- Try it again. Still happens.

- Try search in a different browser. Still happens.

- Shit, I’ve been hacked.

sshto my server. Because I use Movable Type as my blog software, there are physical HTML files on disk for all my blog entries. Looking at the source code that should have been served up showed nothing unusual.- Examine the .htaccess file for my site. This is where the damage was being done. The .htaccess file controls things like redirects, and a bunch of code had been added to mine. Interestingly, it was checking the referer on each incoming HTTP request, and only redirecting viewers that had come from a search engine. If you typed “http://sunpig.com/martin” directly into the address bar of your browser, or if you arrived via a bookmark or a non-search engine link, you would be let in as normal. The hack was designed purely to bleed off search engine traffic.

Next step: find out when the damage was done, and how long this had been going on. The modified time on the .htaccess file was very recent – just an hour previously, in fact. It seemed unlikely that I had caught the hack so quickly after it had happened.

I logged in to my host’s control panel, and checked the account access logs. These logs showed that no-one but me had logged in to my account using ssh or the control panel in the last month. Good. I changed my account password anyway. I also notified my host, and told them what I’d found so far.

I used the unix find command to see what files had been changed in the last 7 days:

find . -mtime -7This showed a bunch of files I knew I had changed or added myself, some log files that I would have expected to be changed, and also: a stack of .htaccess files where there should not have been any, a bunch of unfamiliar PHP files all called “pagenews.php”, and two “index.php” files that I shoud not have been altered in the last week.

Next, I identified all .htaccess files in my account, and all files called pagenews.php:

find . -name ".htaccess"

find . -name "pagenews.php"Then I looked for common text signatures in the files, to see if there was anything else I was missing:

grep -r "on\.ru" .

grep -r "FilesMan" .Okay, infection identified. I could clean up the affected files, but I still didn’t know how the attacker got in in the first place. Without knowing that, there would be nothing to stop them getting straight back in again.

The time stamps on all the affected files went back three days. Some were stamped today, some were stamped yesterday; only one dated back to Monday. I checked the Apache log files of web traffic, and found that yesterday’s time stamps matched up with unusual HTTP POST requests to the two index.php and pagenews.php files. Those files used some kind of obfuscation, so I couldn’t figure out what they were actually doing; but the fact that the file timestamps matched the web access logs, it seems like a reasonable assumption that those POST requests were actually writing files on my server.

However, the one index.php file with a timestamp of Monday didn’t have a matching entry in the HTTP logs. I checked the file permissions, and found that they were set to 666: readable and writeable by everyone on the server.

So my working theory was: at some point on Monday, a process owned by some other user on the same server process on the shared server discovered that I had an index.php file ripe for taking over. It injected the malicious code, but didn’t do anything else immediately. Then, on Tuesday, some other part of the attack kicked in, and started making HTTP requests to the infected PHP file. Because the affected PHP code is running under my account now, it’s free to muck around with other files that belong to me. So the infection spreads to other areas around my server…

Recovery steps:

- Remove the newly created pagenews.php files. Manually remove the infection code from the index.php files, and the .htaccess files. (The .htaccess files were modified, not overwritten. The malicious code was added to the start and end end of the file.)

- Lock down permissions on all files and folders in my account, so that no-one else on the shared server has permission to write to them.

- Remove unused code (old versions of Movable Type, Thinkup, lessn, inactive dev sites) to minimize attack surface for the future.

To recursively apply 755 permissions to directories, and 644 permissions (read/write by me, read-only by others) to files:

find . -type d -exec chmod 755 {} \;

find . -type f -exec chmod 644 {} \;Steps for the future: run a scheduled backup job for static files on the server. I already use autoMySQLBackup for daily backups of the databases on the server, but clearly I need to consider the static files, too. Vasilis van Gemert has an example here: https://gist.github.com/2415901.

Lessons learned:

- If you’re running on a shared server, make sure that your files are not writeable by others on that server.

- Backups. It’s not a matter if if something goes wrong, it’s a matter of when. My home backup strategy is pretty solid; my server backups are still lacking.

Walking through London

I just finished reading Kate Grifin’s The Midnight Mayor, and last week I read Christopher Fowler’s Bryant & May Off The Rails. Both books are love letters to London. They revel in the thick layers of history, above ground and below. The city is a living thing, metaphorically for Arthur Bryant and John May, and literally for Matthew Swift, the protagonist of Kate Griffin’s series. In both cases, the city can be angered or appeased, coaxed and cajoled into giving up its secrets. Bryant and May, detectives, discover a vital clue in the different patterns of upholstery used on the Underground’s 12 lines; Matthew Swift, a sorcerer, uses the Underground’s terms and conditions of carriage as a powerful magical ward to defend himself.

I just finished reading Kate Grifin’s The Midnight Mayor, and last week I read Christopher Fowler’s Bryant & May Off The Rails. Both books are love letters to London. They revel in the thick layers of history, above ground and below. The city is a living thing, metaphorically for Arthur Bryant and John May, and literally for Matthew Swift, the protagonist of Kate Griffin’s series. In both cases, the city can be angered or appeased, coaxed and cajoled into giving up its secrets. Bryant and May, detectives, discover a vital clue in the different patterns of upholstery used on the Underground’s 12 lines; Matthew Swift, a sorcerer, uses the Underground’s terms and conditions of carriage as a powerful magical ward to defend himself.

I’ve never lived in London, only visited, and so I only know it through the eyes of a tourist. But my most vivid memories of the city are of walking through it, not of the shopping or glitzy attractions.

I’ve never lived in London, only visited, and so I only know it through the eyes of a tourist. But my most vivid memories of the city are of walking through it, not of the shopping or glitzy attractions.

Walking around Covent Garden when Abi and I took the train down from Edinburgh on day in the late 90s, just to have lunch at Belgo’s, and coffee with James. Walking from my hotel near Victoria to the QEII conference centre in the mornings and back again in the evenings, in June 2006 for the @Media conference; a steady soundtrack of At War With The Mystics by The Flaming Lips on my iPod. Walking from Waterloo to the Tower with Abi & the kids, and Jules & Becca; deciding that we were too tired to visit, so camping out at a nearby Starbucks for a cool frappucino instead. Walking from Victoria to Southwark last September for lunch with Bora, because it was a glorious day, and I had the time; gazing up in awe at the Shard under construction.

I’m more than a little tempted to plan a holiday in London solely for the purpose of walking the city, North to South, East to West. Not planning for any stops along the way; just taking it as it comes. Getting underway before dawn, and watching the city come to life around me. Lunch from a sandwich shop, dinner from a chippie. I don’t know how far I’d get, or what I’d see; I don’t actually know the city that well; but that’s part of the point. To walk, to see, to be.

Bookmarks, the physical kind

For bookmarks, I like using markers of a time and place: bus, train, and plane tickets; cinema or concert tickets; significant receipts, especially from holidays; appointment cards; other people’s business cards, just after I met them.

After finishing the book, I leave the marker in the book for my future self to discover, years later, and to remember the circumstance of the journey or meeting. Sometimes fondly, sometimes not at all.

A responsive experience begins on the server…

…But it doesn’t end there.

On MobiForge a few weeks ago, Ronan Cremin pointed out that most top sites use some form of server-side detection to send different HTML to different devices. In a follow-up article, he takes Google as a specific example to show just how widely its content varies between an iPhone, a BlackBerry Curve, and a Nokia 6300.

I’m not arguing against server-side detection, and sending different content to different devices. I think it’s an essential part of an adaptation strategy. But I just want to quickly point out a few reasons why it’s not enough in order to cover the whole spectrum of browsers. Here are a few things that you won’t know when a browser makes its first request to your web server:

- The height and width of the viewport being used. (Including the device’s portrait/landscape orientation.) If you detect a mobile device, you will be able to look up the device’s “standard” dimensions in a device database, but the user’s actual viewport may be different. If you place a web app on your iPhone’s home screen, and run it without browser chrome, it will send the same user-agent string as when it is running in a browser with chrome (thus reducing the available height). The user may be viewing your site in a browser panel embedded in a separate app, which may present a different viewport. As Stephanie Rieger explained in “Viewports all the way down…“, anyone can create embed a web view of arbitrary size in a home-made ebook.

- The zoom level. Lyza Gardner wrote about how zoom levels and different text sizes can mess up pixel-based responsive layouts. A user-agent string contains no information about whether a user has changed the default font size in their browser. It does happen, and probably more often than you think.

- Whether the user has cookies, and/or JavaScript enabled. I mentioned some of the reasons people disable JavaScript last year. I think that on mobile devices, which are commonly bandwidth-capped and/or rate-limited, people have a greater than normal incentive to disable JavaScript. (I don’t have any statistics to back this up, though; it’s just a feeling.) Lack of JavaScript can play havoc with some client-side detection techniques. (And lack of cookies will trip you up in many more ways; treat that as a general personalization problem.)

Basically, just because the user-agent string says “iPhone” doesn’t automatically mean you’re dealing with 320 x 480. Server-side detection alone will not give you the full picture, and only doing adaptation client-side robs you of the opportunity to perform really useful server-side optimizations. The best approach is a blend of the two, as Luke Wroblewski describes in “RESS: Responsive Design + Server Side Components“.

RESS is MORE.

Further reading:

Uploading photos from iPhoto (11) to Flickr

I used to use the Flickr Uploadr tool a lot to upload photos to Flickr, but over the last year or so I’ve found myself doing it less and less — even to the point of wondering if I should keep up my Flickr Pro membership. I think this was because I started using iPhoto. I don’t used iPhoto a lot, but adding one more tool to my photo workflow was enough to make the act of working with photos a burden.

Before iPhoto, my workflow was:

- Copy photos from camera memory card onto my computer

- Rename folders & organize photos into archive structure

- Use Flickr Uploadr to upload photos from hard disk to Flickr, setting correct rotation, photo set and tags

- Go to Flickr to add photos to the map. Maybe add some titles manually.

iPhoto never simplified these steps for me. It only added to them:

- Import photos into iPhoto

- Use iPhoto to organize photos into events, and set the correct rotation. Maybe add some titles manually.

Over time, I drifted into the habit of only placing photos into my own archive and importing them into iPhoto, and skipping the steps of uploading to Flickr. Flickr is not a bad tool by any means, but rotating and sorting in iPhoto is much faster and more immediately rewarding. The extra effort of doing all this again for Flickr put me off doing it at all.

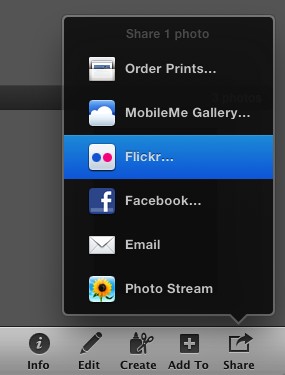

However, at some point in the past, I must have noticed that iPhoto allows you to connect a Flickr account. (Go to iPhoto → Preferences → Accounts, and you’ll see the option to add Flickr, Facebook, MobileMe, and Email accounts. Selecting Flickr will take you to the Flickr website, where you can authorise iPhoto to post photos to your stream on your behalf.) I just didn’t do anything with this option until yesterday, when I discovered the “share” button in the bottom right corner of iPhoto:

From here, you can add the selected photos to an existing Flickr set or create a new one. You can set the usual privacy options, and you can choose whether to upload a scaled-down image or the full version.

This means that I can organize all of my photos in iPhoto, rotate them, name them, add descriptions, set a map location, etc.; and then push them up to Flickr at the press of a button. No added effort. Awesome. This is a workflow I can live with.