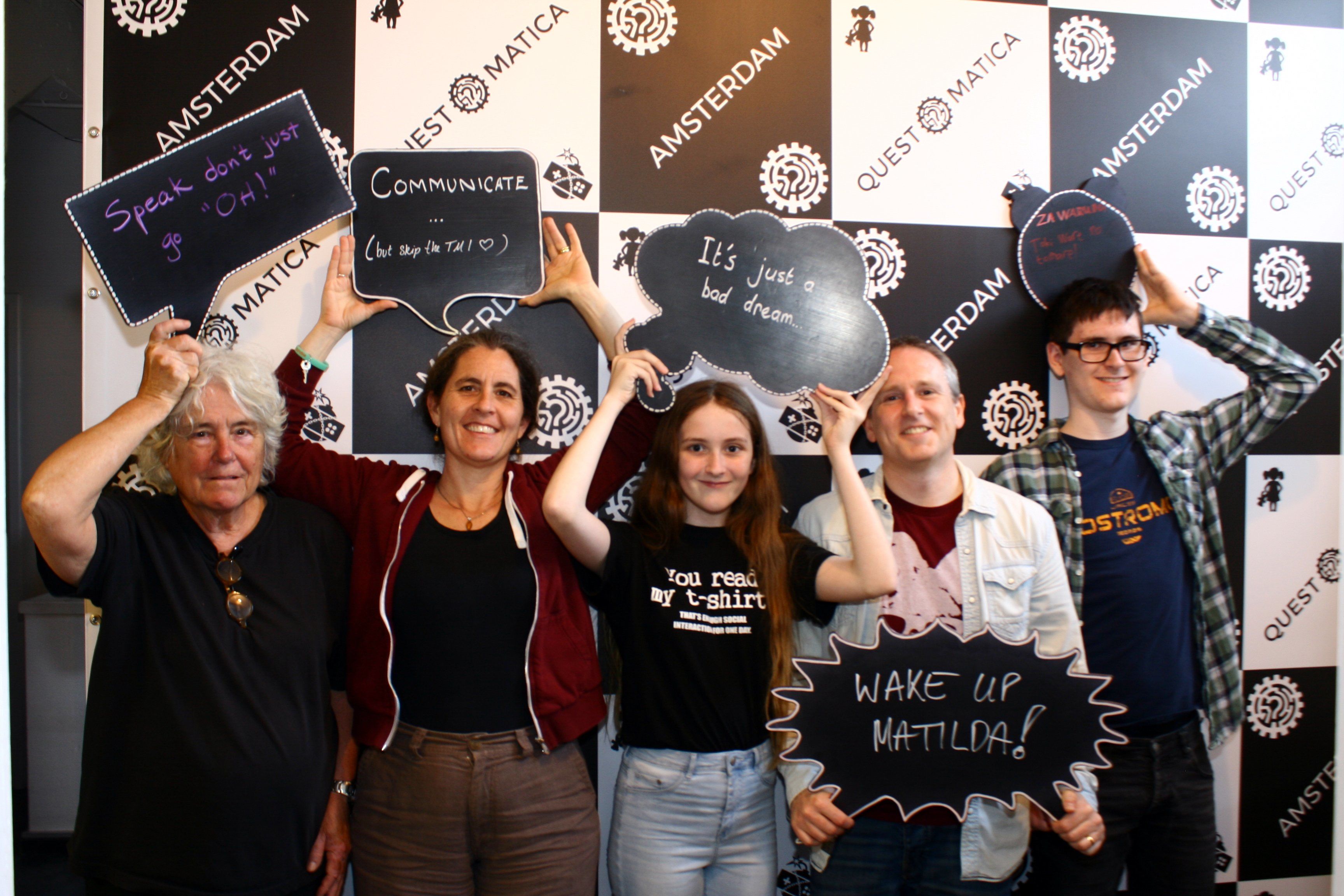

At the start of May when Susan was visiting we took a family trip to Amsterdam to do an escape room. We went to the “Wake up!” adventure at Questomatica on the Foelistraat. I don’t want to give away plot points, so I’ll just say that it was excellent. Alex has done an escape room game at school, but for the rest of us it was our first time. We’re all seasoned video game puzzelers, but the thrill of being right inside the puzzle was a great sensation. I don’t know if “Wake Up” is a representative example other escape rooms, but take on its own I thought it was well-constructed, challenging, with a theme that kept us engaged and excited all the way through. Highly recommended!

Mixed Media, Sunday 4 June 2017

Games:

- Horizon: Zero Dawn: Amazing — one of my favourite games of recent years. It took over my whole life for about two months. Loved the action, loved the story.

TV:

- 12 Monkeys season 1: Entertaining enough that I’ve continued with season 2.

- Westworld season 1: Very good! Just as Jonathan Nolan’s show Person of Interest looked at the intersection of surveillance and AI, and tried to figure out what the endgame was, with Westworld he looks at video games and AI and speculates about where that could go. It made me think a lot about the kind of games I enjoy playing, and the paths I like taking through them.

- Iron Fist season 1: Bad, for all the reasons you’ve probably already heard about.

Films:

- Hell of High Water: good, cautiously paced, tense, thoughtful

- Hardcore Henry: bonkers in a good way

- Mechanic: Resurrection: bigger in scope and budget than the first one, but with less heart. Some amazing action, though.

- Ghost In The Shell (2017): visually spectacular but dramatically flat

- Ghost In The Shell (1995): really weird and interesting

- Fast and Furious 8: double-plus bonkers, again in a good way

- Guardians of the Galaxy vol 2: fantastic, although it doesn’t get better than dancing Groot in the opening scene.

- Jack Reacher: Never Go Back: sure, whatever

- Alien: Covenant: fine, but predictable

- Hunt for the Wilderpeople: offbeat, funny and sweet

Books:

- Runaways vol 1 by Brian K. Vaughan, Adrian Alphona, and Takeshi Miyazawa: outstanding

- A Closed And Common Orbit by Becky Chambers: quiet sequel to The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet. Good, but didn’t leave me with quite the same fuzzies. Feels like a side quest.

- The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl vol 5: Like I’m The Only Squirrel In The World by Ryan North, Erica Henderson et al.: still good!

- Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States by Albert O. Hirschman: amazing. I’ve been talking everyone’s ears off about this. Written in 1970, it’s short but very insightful, with tons of relevance for modern politics, customer relations, economics, and employment.

- Saga vol 7 by Fiona Staples and Brian K Vaughan: Saga has never really been sunshine and puppies, but this volume is really dark and sad. Art and storytelling is still amazing.

Marianas Trench at Tolhuistuin (Paradiso Noord), Thursday 18 May 2017

This gig had originally been scheduled for 11 October 2016, but was postponed because Josh Ramsey’s came down with laryngitis. When they started playing “Astoria” I was concerned about how this one was going to turn out, because his voice sounded rough and shaky. He warmed up quickly in the first two numbers, and was fine after that. Much jumping and prancing. Fiona had been quite shaky herself that day, and only decided to come along with me at the last minute. She made it all the way through the gig, though, and we had a good time. (As part of the inevitable merch haul, I got another signed drum head. Is this a thing that bands do now? If so, I’m totally fine with it.)

Set list:

- Astoria

- Yesterday

- Celebrity Status

- Burning Up

- All To Myself

- Here’s To The Zeroes

- One Love

- This Means War

- Desperate Measures

- Fallout

- Stutter

- Pop 101

- Who Do You Love

- Cross My Heart

- Good To You

- Haven’t Had Enough

- End Of An Era

The chickens are coming

Family trip to Berlin, April 2017

While Susan was visiting us this year, we took a trip to Berlin! I had never been there before, but had heard lots of good things about the city in recent years.

We flew to Schönefeld early on the morning of Thursday 27 April. We took a train into town, and met Abi on the way. (She had gone there a few days earlier for a conveniently timed work trip.) We had a hotel on Anhalter Str., just a couple of blocks away from Checkpoint Charlie. After dropping our bags, we walked round there, and had lunch at the McDonalds overlooking the checkpoint. (Rather: everyone else had McDonalds. I had a currywurst next door.) In the afternoon we took a bus tour to give us an overview of the city. Later in the evening, when everyone else was tired, Abi and I took a walk up to Potsdamer Platz and the Brandenburger Tor.

The next day, Abi and Fiona had booked themselves on a street art tour and workshop, while Alex and I visited the computer games museum. The following day Fiona was struggling, and she and I stayed in our room most of the day. In the evening Alex, Fiona, and I did make it out to see Guardians of the Galaxy at the Sony Centre, though. On Sunday Abi and I went out for a little wander before we checked out. Then we all then parked ourselves at a café opposite the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, from where we mounted various small expeditions until it was time to head to the airport for our flight back.

Overall impression: Berlin is a beautiful city, and I want to go back. The sensation of history of the place had a big impact on me while I was there. The city’s pride over being at the heart of modern European politics also shines through. Also, the scale of the place is huge. Some of the streets felt like they were built for giants, and underground stations often felt empty, like they had been built for a city with ten times the population. Thumbs down on Schönefeld airport, though. Nice public transport connections, but the facility itself is a hard-to-navigate dump.

Edinburgh Avengers

Walking up the Bridges back to my B&B in Edinburgh late one evening in April I spotted activity on the High Street. Turns out a film crew was shooting scenes for the new Avengers film! I stood around behind the barriers for a while and watched the crew at work. Conclusion: 80% of your time on a big budget film set is spent standing around waiting for things to happen. Every now and then the marshalls would hear an announcement on their ear pieces and call for everyone to be quiet. The cameras were half-way down Cockburn Street, though, and the barriers were well up on the High Street, so I couldn’t see much. I caught a few glimpses of people in odd-looking uniforms with what looked like thin poles sticking up from their backs, but mostly I just found it fascinating to observe all the peripheral effort that was going on: wind machines being trundled around; a guy hosing down the street; the huge crane-mounted lighting rigs that must have made midnight look like daytime. Lots of pizza and food boxes being delivered for the crew. At one point a big black SUV with tinted windows passed by and the marshalls gave the crowd a big knowing grin. He didn’t say anything, though.