For all the time and money I spend on Amazon.co.uk, it’s actually quite rare for me to take the advice of one of their “recommendations”. But after finishing Charlie Stross’s Singularity Sky, I was in the mood for some more punchy SF, something with a good bit of action and a hard-edged futuristic bite to it. And apparently, customers who bought books by Charles Stross also bought books by Neal Asher.

For all the time and money I spend on Amazon.co.uk, it’s actually quite rare for me to take the advice of one of their “recommendations”. But after finishing Charlie Stross’s Singularity Sky, I was in the mood for some more punchy SF, something with a good bit of action and a hard-edged futuristic bite to it. And apparently, customers who bought books by Charles Stross also bought books by Neal Asher.

I’d seen the name before. I’d picked up his books in bookshops, and been intrigued by the fabulous covers (on the UK editions, at least). I’d seen his name regularly mentioned in the same breath as Richard Morgan, whose books I like really quite a lot. So I clicked through, and bought Gridlinked.

I find there’s a great pleasure in coming across an author I like when they are already several volumes into a series, because then I can go out and gobble up all the episodes so far in a single reading binge. Such was the case with Neal Asher. After a few pages of Gridlinked, I was thoroughly hooked, and I ordered The Line Of Polity and Brass Man, the second and third books in the Ian Cormac series straight away.

I find there’s a great pleasure in coming across an author I like when they are already several volumes into a series, because then I can go out and gobble up all the episodes so far in a single reading binge. Such was the case with Neal Asher. After a few pages of Gridlinked, I was thoroughly hooked, and I ordered The Line Of Polity and Brass Man, the second and third books in the Ian Cormac series straight away.

As far-future thrillers these books are second to none. Although Gridlinked was only published in 2001, Asher has been writing for twenty years, working his way up through the small presses, and continuously developing the Human Polity universe in which the stories are set. Consequently, they positively brim over with vivid detail and richly characterised planetary societies.

The Skinner and Cowl are both stand-alone novels. The Skinner is set in the same Polity universe, but several hundred years earlier. It’s a novel of grisly exploration as much as a thriller, as it leads you through the terrifying world of Spatterjay, where immortality is for the taking–at a price–and where even the smallest seashore whelk has a bite that will take your hand off. Cowl is an inventive time travel thriller set in a completely different universe, but with the same characteristics of Asher’s other books: fast action, tight plots, horrific enemies, and danger at every corner. You want science fiction excitement? Come and get some.

The Skinner and Cowl are both stand-alone novels. The Skinner is set in the same Polity universe, but several hundred years earlier. It’s a novel of grisly exploration as much as a thriller, as it leads you through the terrifying world of Spatterjay, where immortality is for the taking–at a price–and where even the smallest seashore whelk has a bite that will take your hand off. Cowl is an inventive time travel thriller set in a completely different universe, but with the same characteristics of Asher’s other books: fast action, tight plots, horrific enemies, and danger at every corner. You want science fiction excitement? Come and get some.

Like many SF authors these days, Neal Asher has an active presence on the internet, running two sites: the official one, nealasher.com, and an alternative view at his older personal site. When I posted my quick review of Gridlinked, he dropped by to leave a kind thank-you comment in response. Unwilling to let a good deed go unpunished, I asked him if he would do a short email interview for this blog, and he graciously agreed. I hope you enjoy it.

Martin Sutherland: From the reviews I’ve seen, Brass Man is getting a great reception. How big is the difference between the attention you’re getting now, and when Gridlinked was published in 2001? How do you find yourself reacting to all this praise?

Martin Sutherland: From the reviews I’ve seen, Brass Man is getting a great reception. How big is the difference between the attention you’re getting now, and when Gridlinked was published in 2001? How do you find yourself reacting to all this praise?

Neal Asher: Strangely, I’ve seen fewer reviews of Brass Man (thus far) than I saw of Gridlinked and The Skinner when they came out. I think, in the reviewing world, there’s an attraction to the sparkly new thing, which I was then to the larger publishing world, but which I am not so much now. Now I’m part of the establishment. How do I react to the praise? I revel in it, but I’m much more reserved in my attitude to the reviews because, having had so many, I can pick up any one now and find another that flatly contradicts it. The same rules apply to people’s attitudes to my books. Initially The Skinner seemed to be everyone’s favourite, now I’m finding that each one of them is someone’s favourite. Luckily I get very few saying how much they really hate this or that. But what affects me most of all now is the increasing amount of fan response I’m receiving (both by email and on message boards). When someone writes to thank me, saying they picked up one of my books, didn’t put it down until 3.00 AM and are now going to go and get the rest, I feel pretty good. This is the effect some books had and still do have on me, and is precisely what I’m aiming for.

MS: I know you pay attention to mentions of your books on the internet, because that’s how you came across my tiny wee review of Gridlinked. Do you go out of your way to seek out reviews in newspapers and magazines? Do you have any particular favourite, or least favourite reviews? And have you counted how often the word “explosive” turns up whenever someone talks about your books?

NA: I don’t go too much out of my way to find the reviews. When a book is released I flick through a few magazines and if I find something, buy the magazine, cut out the review, and add it to my scrap books. Internet reviews are easy to find with an ego-search on google. Whenever I find them I feel beholden (if possible) to reply, for that is the least I should do if someone has made the effort.

Very often the words explosive, action-packed, violent, weird etc appear in reviews, and that’s great. I’ve always said I come from the Arnold Schwartzenegger school of SF. My aim, firstly and most importantly, has been to tell an entertaining story, not stun literati minorities with my brilliance.

My favourite review has to be the one of The Skinner that appeared in the New York Times. To begin with it was very good, but it what a venue!

MS: In an earlier interview you had said that you had originally intended to write four Ian Cormac books, one for each Dragon sphere, but that seems to have gone out the window now. At what point did you feel that you needed more space to tell all of these stories?

NA: That had been my intention, and it seemed obvious to many, from what happened in the first two books, that this was they way the rest were going to go. I tend to find in my writing that when I know myself what is going to happen I get bored, and it becomes more difficult for me to write. I got bored with that idea and new ones began to occur. A lot of people commented about how they really like Mr Crane … and a whole book came out of that. I also introduced Jain technology… As things have continued I’ve realised I need more than four books to tie up the loose ends, firmly nail down certain ideas and give a clearer description of the Polity. In the end, when you are describing a future history, the job can be never ending. Books about Cormac will reach a conclusion, but I suspect I’ll be writing about the Polity for a long time yet.

MS: Your novels so far have alternated between stand-alones, and volumes of the Ian Cormac series. What do you find are the main differences between writing the two types of book?

NA:The stand-alones are easier to write and I can allow my imagination a freer rein. The series is constrained by everything I’ve written before. Writing the series is more difficult because I have to keep going back to the old books to check my facts and iron out continuity errors.

MS: You’re now doing a book every nine months, rather than the more usual one per year. Is this pressure from your publisher to get hot product onto the shelves, or are you just writing faster than they can keep up with?

NA: The latter case. I’ve always delivered my books many months before I’ve needed to, and the gap has been growing ever wider. It has now reached the stage where I’m about a year ahead of my publisher. They’ve decided to play catch-up and adjust the publishing schedule to suit me more. Of course it helps that my books sell.

MS: Hubris is a big theme in your work. Not only is it the name of the main attack ship in Gridlinked, but it is also a motivating force for your

villains: Arian Pelter and Skellor are both arrogant enough to think that they are uniquely capable of controlling a dangerous thing that is quite obviously greater than themselves. It’s a classic theme, and also a very British one: we don’t like people getting too big for their boots. Do you feel that there are any other aspects of your work that are specifically British? And more generally, to what extent do you feel that your environment and current events shape your writing?

NA: A villain’s hubris bringing about his downfall is a quite commonly used plot-device. It’s especially useful when the villain is very powerful—a form of krypyonite really. I have to say though that I don’t think it a particularly British idea since it’s rooted into the mythologies of the entire human race. In fact I rather dislike the idea of being diagnosed as infected with that very British disease which is plain envy, not just a dislike of “people getting too big for their boots”. But I guess by Britishness comes out in my writing in many ways. How can it not? The great thing about SF writing is that everything feeds the mill: current events, some article in Focus or Scientific American, a fragment of conversation in a pub or something you saw crawling out from under a rock.

MS: The complementary theme is, of course, justice. The Gridlinked books follow the adventures of ECS agent Ian Cormac, and The Skinner and Cowl both feature characters chasing down mass murderers. You also seem to relish in making sure that bad guys get their righteous comeuppance. What do you think draws you to this kind of story, and this kind of character?

NA: Contrary to what is often seen in British writing—that dystopic vision of everyone screwing up, including the main character, and it all turning to shit in the end—I want to see the white hats win and the black hats dangling from the end of a rope. I can do this because I am telling a story, not trying to make serious predictions about the future, or come out with some deeply intellectual social commentary. As a writer you write what you like to read, and that’s what I’m doing.

MS: Your aggressive wildlife is as much of a trademark of your books as your fast-paced action plots. How much do you find yourself tailoring the flora and fauna of your settings to fit your stories, and vice versa?

NA: Usually the flora and fauna begin as world-building—the canvas on which the story is painted—but such is my interest in biology and the weird life forms I create, they often end up playing more of a central role: canvas plus quite a lot of the paint. Take The Skinner: without the ecology of Spatterjay there would be no story. It is all based on that viral immortality and what it does to people. Elsewhere it remains window dressing, but the focus of my attention as a writer is evident when people come away from a novel like The Line of Polity talking more about gabbleducks and hooders than the main characters and plot.

MS: Another technique you seem to be an expert at is rounding up all your characters into a single location for a huge show-down finale. You have said elsewhere that you try not to plan your novels ahead too much, though. Does this tying together of plot strands come naturally, then, or do you have to work hard at it?

NA: A bit of both really. Creating all the plot strands I find very easy, but satisfactorily tying them all off at the end comes a bit harder. My emphasis there is on the ‘satisfactorily’. It is easy to tie off plot threads say by killing all the main characters (the cop-out used in Blake’s 7) or by introducing that old SF standby the deus ex machina—something used by many authors who have backed themselves into a corner and found no other way out. But to bring about an ending that seems to arise naturally from everything that has already occurred and doesn’t leave the reader feeling cheated is a finely balanced thing. Yes, I do find this hard work, but also enjoyable, and years of writing experience oils the bearings. I sometimes fear that this time I’ll not be able to pull it off. Maybe without that fear I wouldn’t be able to?

MS: After Ian Cormac, I think John Stanton is my favourite character. Are we likely to see any more of him?

NA: John Stanton needs a rest and I think deserves to live happily ever after. Don’t you?

MS: Since reading Gridlinked, every time I see someone with a behind-the-ear bluetooth headpiece for their mobile phone, I can help thinking “aug“. Do you like techie gadgets like phones, PDAs, iPods? How do you see these devices influencing our culture? Do you think there is a danger of them dehumanizing our interactions with other people, in the way that had happened to Ian Cormac at the start of Gridlinked?

NA: I recently did an audio interview with Dragon Page which was going to first go out as a ‘podcast’. I didn’t know that that was. I don’t own a mobile phone since I’ve never seen the need. However, this computer is a wonderful writing, research and advertising tool. I do love technology for its own sake, but not enough to go out buying the latest gadget on the market. I will use whatever technologies best serve my own purposes.

I’ve always been optimistic about all technology. Yes, some of them have the capacity to dehumanize our interactions with other people, for example the text messages : You’re fired, or You’re dumped. But on the whole they tend to enhance communication. We’ve many different ways now of chatting with anyone anywhere. The old and/or the crippled confined to their houses can now have that option. We tend to talk and interact more now, not less. This interview is an example.

MS: The inevitable movie question. At a talk Richard Morgan gave a couple of years ago (after he’d optioned the rights to Altered Carbon), I remember him saying that one of the keys to attracting Hollywood’s attention is a fast-moving plot, plenty of violence, and a strong headline protagonist to carry it all. It sounds like the Gridlinked series would fit the bill. Have you had any interest from Movieland? Which of your books (if any) would you most like to see turned into a film?

NA: There was a brief bit of interest from a production company called Blue Train (I think that’s the name) who along with another company called DreamWorks (!) were involved in the Jackie Chan movie The Tuxedo. But nothing came of it. I still live in hope, however.

With the CGI we have now I’d love to first see The Skinner turned into a film, then my second choice would be Cowl. The Cormac series I reckon would be much better serialized for television, though of course I wouldn’t be averse to them being turned into films (Heh!)

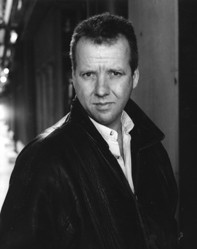

MS: Leather jacket with the collar up, white shirt casually unbuttoned at the top, and a casual frown that says, “I know 27 ways to kill you with my bare hands.” So what do you think of your author photograph?

NA: Hah! That was an interesting experience. Met a photographer, employed for the task by Macmillan, called Jerry Bauer. He’d photographed all sorts like Julie Christie and James Dean. He talked about Robert Silverberg and when I repeated the name he asked, “Do you know Bob?” Well yeah, me and x-million other SF readers. He took myself and my wife off from Temple underground station and had me posing in various litter-choked alleys while he took his snaps. My wife, Caroline, found much amusement watching the reactions of passers-by.

I don’t know 27 ways to kill someone with my bare hands, just variations on about five or six—as does anyone who has done a bit of karate. However I probably do know about 27 different ways to run away. That picture is now getting on for six years old. I’m a bit greyer now and baggier under the eyes. A bit wiser too, I like to think.

Brass Man is Neal Asher’s latest book, out now in hardback and trade paperback, published by Tor Books UK.

Copyright © 2005 Neal Asher and Martin Sutherland