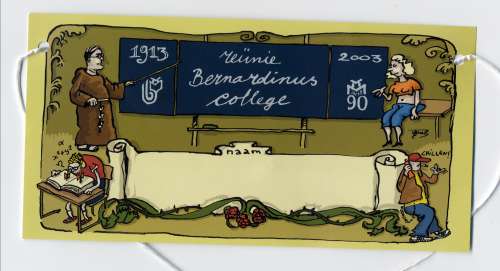

It was my high school reunion last week. Wow. It wasn’t a reunion specifically for my year, but rather a party for the whole school, which is now 90 years old. Several thousand former pupils and teachers showed up for the evening, and the entire school was packed out with people going, “Great to see you! So what are you doing now?”

I was having a lot of mixed feelings about going back. First of all, I’m not a very social person. Given the choice between going out to a party, or staying home and reading a book, I’ll take the book almost every time. I have an odd condition called “obscure auditory dysfunction,” which means that despite having perfect hearing under normal conditions, I have some difficulty making out speech in noisy environments. I could be charitable and say that this is what makes me uncomfortable in party situations, because I can’t hear half of what people are saying to me. Generally, though, I figure that I’m just a crotchety bastard who doesn’t like people.

Also, until the end of last year, I had completely lost touch with everyone from my class. This was all my fault. A Christmas card each year, and a postcard or two to communicate address changes is hardly a great effort, but it was still too much for me. Re-establishing contact with someone means admitting that you lost contact in the first place. In the grand scheme of things, it’s a tiny embarrassment. But after a certain amount of time had gone by, I found it easier to live with the personal guilt of losing touch, than to deal with the interpersonal shame of admitting my incompetence as a correspondent.

I left school in 1989, and I lost touch with my last set of school friends (Marco Linden and Ineke Linden-Brümmer) in about 1996. (All my fault. I didn’t follow up on an address change, and now Marco and Ineke are somewhere in Africa, practicing tropical medicine…I think. If anyone knows where they are, please drop me a line.) For a few years after that, I would have found it too awkward and socially painful to contemplate a reunion, if one had taken place.

But time is a damp sponge that wipes many slates clean. After a certain amount of time, I found myself wanting to find people again, and to reconnect to my friends from back then. I started doing web searches to see who I could find. In November of last year I came across Evert-Jan, who was in touch with several others from our old gang, and so the first set of links was established. In June of this year I found an email address for Olga, who has been a friend since primary school, and who was instrumental in bringing Abi and me together. (A story for another occasion, perhaps.) Olga was in touch with a different knot of contacts, and we joined the two chains together. By the time the reunion came around, we had about twenty classmates on the list.

Next in the list of sources for mixed feelings, there’s the problem of language. My old school is in the Netherlands, you see. I grew up there. I was six years old when we moved to Voerendaal; my brother Scott was four. We both attended Dutch primary schools, and we picked up the language very quickly. We only spoke English at home, and Scott and I even started speaking Dutch with each other. We still do. Although we spoke and read English at home, we both learned “formal” English (grammar, etc.) as a foreign language at a Dutch high school. In many ways, Dutch is our first language.

Or at least, it was.

After finishing high school in 1989, I moved to St. Andrews to go to university. I went back to see my parents in the Netherlands during the holidays, but less frequently as the years progressed. Scott also moved back to Scotland, and went to Stirling to study psychology. Abi and I got married in 1993, and we set up house in Edinburgh. My parents moved back to Scotland in 1995. With all of my family back here, and having lost contact with almost all of my school friends, I have very little reason to go back to the Netherlands on a regular basis.

Consequently, my Dutch suffered. Enormously.

I can still understand spoken Dutch easily enough–that was never a problem. Because Scott and I still speak Dutch to each other (although by now it’s more of a personalized English/Dutch creole), I have retained a certain amount of fluency in speaking the language. I still have a Limburgs accent, for example. I’ve lost a lot of idiom, though. When speaking with Scott, if I can’t think of a Dutch phrase quickly enough, I’ll throw in the English version, rather than waiting or asking him if he knows the right expression.

Written Dutch is a different matter altogether, though. I can still read Dutch perfectly well, just much more slowly than I used to. Written language generally uses more complex grammatical constructions than spoken language does. Sentences are longer, and people are inclined to use longer and rarer words than the ones that roll happily off the tongue in free-flowing everyday speech. I have to concentrate to read Dutch newspapers. (Weblogs are an interesting cross between formal written language and informal conversations, and I’ve been reading a couple regularly to try and increase my reading fluency.)

As for writing Dutch…. Aargh. Now that’s really difficult. When I was getting back in touch with all of these friends through email, it took a lot of time and effort to construct even the most basic paragraphs in reasonably grammatically correct, simple Dutch. A few times I had to revert to English just so I could finish an email in a single evening.

Forgetting a language you once knew very well (I was editor of our school magazine, for goodness’ sake) is strange, and more than just a little scary. There was a point last weekend where I went into a bakery to buy some pastries for a late breakfast. The bakery shelves were filled with delicious sweet things I recognized from my childhood. But I could not remember what any of them were called. The price list behind the counter showed the names of all the pastries: hanekammen, nonnevotten, moorkoppen, and lots more. But the words were meaningless to me. Even with the items themselves right in front of me, I couldn’t make the mental connection between the pastries and their names.

I suddenly had a glimpse of what it must be like to be suffering from dementia, or to have some other form of brain damage. It chilled me.

All of this, then: the reluctance to socialize, the embarrassment of having lost contact, and the awkwardness of not being able to speak the language properly; they all contributed to make me feel uneasy and uncertain about going to the reunion.

The last major factor is change, or at least the fear of change. How much would people have changed? Would we still have anything to talk about? Would we still have anything in common, apart from our memories of school? Would we even still recognize each other?

My fear was partly allayed, and partly exacerbated by our visit to the Netherlands a month previously, at the end of August. On the one hand, while we were driving around Voerendaal and Heerlen (the nearby town where the school is located), I was so freaked out by some of the changes that I had to stop and let my dad take over the driving. What are those houses doing there? Where did the road go? There’s a shopping centre there? Where are we? Help!

On the other hand, Abi, Alex and I took some time out to go and visit Olga and her husband Hans. I was nervous before seeing her, but the visit was wonderful, and very reassuring. Apart from being pregnant, and looking a bit narrower in the face (and more like her mother), Olga hasn’t changed much. Hans is a wonderful, friendly guy, who was more than happy to play with Alex, and to speak English with Abi. We didn’t pick up our friendship from exactly where we left it ten years ago, but that would have been even weirder. Instead, we talked as adults, as fellow parents and parents-to-be, and as ready-made acquaintances.

If you don’t cultivate them, the bonds of friendship undoubtedly grow weaker with time. Shared history never disappears, but the experiences belong to the people we were then. To us, they are memories. Friendship can be rooted in the past, but it has to live in the present. Its bonds therefore have to reflect the people we are now. That’s probably the thing I feared most: have my old friends and I changed so much that we could no longer become new friends?